Varian Fry was an American journalist who led a rescue network that helped over 2000 Jewish and anti-Nazi refugees, among them many preeminent artists and intellectuals, escape Vichy France. Based in Marseilles in 1940 and 1941, Fry did this at great personal risk. His story is reasonably well-known, having been the subject of several books, an exhibit at the US Holocaust Museum (1993-95), a documentary (1997), and a docudrama (2001). Fry was also the first American designated a “righteous Gentile” by Yad Vashem.

His story was recently retold in Julie Orringer’s historical novel The Flight Portfolio (2019) and the Netflix seven-part docudrama Transatlantic (2023). Working from strong historical evidence that Fry, though married, was a closeted gay, Orringer makes an imagined gay relationship involving Fry a major theme of her novel. (In a review in The New York Times, the novelist and critic Cynthia Ozick – still professionally active and articulate in her early nineties – dismisses Fry’s homosexuality as “movie-tone make-believe.” But a few days later, in a letter to the editor, Fry’s son James confirms Orringer’s interpretation of his father’s sexuality.)

The Netflix docudrama was inspired by Orringer’s novel. While including Orringer’s story of Fry’s imagined gay relationship, showrunners Anna Winger and Daniel Hendler were also looking for human interest stories that would appeal to a larger audience, and they chose to focus on two of Fry’s actual colleagues, the American heiress Mary Jayne Gold, and the young German economist Albert Hirschman.

Smooth Operator

Orringer depicts Hirschman as “perfectly slim, perfectly blond, always dressed as though he meant to conduct a lunchtime romance” and “a smooth operator” (props to Sade). Hirschman’s biographer Jeremy Adelman writes “[Fry] depended on the friendly but mysterious young translator for his underground experiences, facility with money, command of languages, and affection for bending and breaking the rules” (p. 171) and Mary Jayne Gold describes him as “a handsome fellow with rather soulful eyes, standing there taking everything in, his head cocked slightly to one side. One of those German intellectuals, always trying to figure things out.”

It is no surprise that, to balance the gay romance, Transatlantic imagined a straight romance between Hirschman and Mary Jayne Gold. Sadly, they do not fly off into the sunset: she returns to the life of a socialite in the US and he leaves for the US to serve in the war effort and make his career in academe. Improbably, she brought her private plane to Marseilles. They bid a tearful farewell at the airfield, and she climbs into the plane while he stays on the ground – an obvious hommage. As this scene might suggest, Transatlantic received mixed reviews. However, I was particularly fascinated by Hirschman’s story for reasons I’ll explain below.

The Path Not Taken

Hirschman had a peripatetic career as an academic economist, described in both Adelman’s book and in a New Yorker tribute by Malcolm Gladwell. He was as eclectic as he was peripatetic, but the most appropriate pigeonhole was as a development economist. Hirschman was at Harvard from 1964 to 1974.

I was a senior in 1970-71 and had decided to write my senior thesis on free market economics as espoused by Milton Friedman and the Chicago School and the influence of that ideology on monetary policymaking, particularly as enacted by the Federal Reserve.

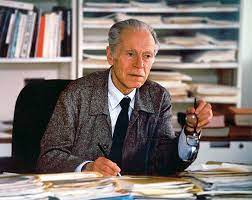

I was looking for an adviser, and someone, possibly the director of the Social Studies Program, suggested I approach Hirschman. Perhaps that suggestion was somewhat mischievous because Hirschman had just published a book (Exit, Voice, and Loyalty) that, to oversimplify, criticized the classic conservative response to underperforming institutions (exit) and praised the contrasting liberal response (voice). I vaguely recall from my meeting over fifty years ago a gentleman in his mid-fifties with a mitteleuropaische accent. Alas, Hirschman wasn’t interested in advising my project.

The adviser I did find – Barry Bosworth – was a young assistant professor with strong technical skills. (Bosworth went on to a distinguished career as a macroeconomist at Brookings). I recall that in the first half of the thesis I almost drowned in the swamp of Chicago School monetarism. However, the second half was based on interviews with public servants and governors at the Federal Reserve and a detailed reading of Open Market Committee Minutes, available at Harvard’s Widener Library. From the interviews, I learned about then-President Nixon’s determination to influence monetary policy to ensure his re-election and the managed conflict, using the language of the Vietnam War, between monetary policy hawks and doves. I explained how the Open Market Committee espoused a goal of contracyclical stabilization, thereby transforming debates between doves and hawks from a war of conflicting ideologies to gentlemanly disputes about the interpretation of economic data. Shortly after I graduated my first academic article, with the grandiose title of “The Political Economy of ‘The Fed,’” was published in Public Policy, a journal based at the Harvard Kennedy School.

My recent cinematic encounter with Austrian actor Lucas Englander’s portrayal of the young Albert Hirschman leads me to speculate about my real-life encounter with the middle-aged person a half-century ago. Had Hirschman been my adviser, would my thesis have been different, perhaps more conceptual than institutional? It is well-known that many people who served in the military or the resistance never spoke of their wartime experiences as young men and women – so much so that it can be considered a meme. But after I handed in my thesis, Hirschman might have taken me out to lunch and told me some of his backstory. I was editing a journal at Harvard Hillel at the time, and I might have convinced Hirschman to let me put some what he told me into print. This didn’t happen, but in the spirit of Orringer’s novel and the Netflix docudrama, I can now imagine that it did.

Leave a Reply