Because of my longstanding interest in architecture, the topic of a recent post, I grabbed Moshe Safdie’s autobiography If Walls Could Speak as soon as it was released. I read it quickly and was inspired.

In the Right Place at the Right Time

The book is easy to read. Safdie is a superb writer, eloquent in explaining, with words and illustrations, complicated spatial concepts. Safdie’s early life is fascinating: he was part of a mercantile Sephardic family that came to Palestine during the British Mandate, but left the State of Israel in its early years, uncomfortable with its domination by Ashkenazi socialists.

Safdie’s family emigrated to Canada and he studied architecture at McGill in the late 50s. His thesis, entitled “A Case for City Living,” envisaged high rise residences that would provide every home with the benefits of a single family dwelling, such as a garden or courtyard. Shortly after graduation Safdie led the team that designed the Habitat 67 residences at Expo 67, Montreal’s World Fair, thus quickly implementing that vision. In Safdie’s words, Habitat 67 “jump-started [his] career” in his twenties and led to offers to design similar habitat projects all over the world. One of the immediate clients for Safdie’s work was Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek, who had new visions for a city that had been reunited after the Six-Day War in June 1967.

Understanding the Practice of Architecture

For a non-architect, Safdie’s book provides a great opportunity to learn about the practice of architecture from a variety of perspectives. Safdie starts by chronicling a week in his life as founding partner of Safdie Architects and taking the reader through its offices and workshop in Somerville, MA, a Boston suburb. His work involves constant communication with colleagues in his firm and with clients, for example a meeting with Mark Zuckerberg and his minions about a major expansion of Meta’s corporate office. But he also frequently visits the firm’s design shop, which is its technological heart.

A second perspective Safdie provides is in his discussion of many of his firm’s major projects. (An iconic image of each is posted on the website, starting with the most recent.) The project stories show the pillars of the profession: the relationship with the client, embodied in the building’s program; the relationship with the wider community, especially for major projects; and the project’s aesthetics, which include both the structure itself, and the way the structure interacts with the physical terrain and built community that surrounds it. Safdie often describes the creativity of conceptualizing shapes of buildings, and then reconceptualizing them to respond to the client’s developing ideas. Some of his stories deal with projects that didn’t get built, either because his firm didn’t win the competition, the client lost interest, or the community was opposed to the project.

A third perspective is Safdie’s role as architectural theorist, or perhaps polemicist, especially when he was on the faculty at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Safdie is a proponent of socially conscious modernist architecture that aims to benefit as wide a public as possible, and a critic of post-modernist architecture, which he sees as “essentially pictorial” with features that “might be considered in-jokes for those sophisticated enough to be in the know” and which, in his view, abandons the social mission of architecture. Safdie published his original critique of postmodernism in a high-profile piece in The Atlantic in 1981 entitled “Private Jokes in Public Places.” Safdie includes Prince Charles among the Postmodernists, arguing that “in his own slightly dotty way, a leading voice for [embracing the urbanism of the past] was the Prince of Wales, urging a return to what made nineteenth century cities great. But nineteenth century cities didn’t have automobiles.” As discussed in a previous post, I concur. As an aside, I searched the scores of books on my Kindle, and this is the only instance I could find of the word “dotty.”

Architecture and Politics in Canada

Safdie has dealt with many politicians in his career and recognized from the beginning their power to make or break major public projects. The original Habitat 67 proposal was for a $42 million project, to be built by the famous American developer William Zeckendorf, who would receive a federal government research grant. The Finance Minister in the Pearson Government, Walter Gordon vetoed the grant because he didn’t like the precedent it would set. Gordon, an ardent nationalist, likely also objected to the intended recipient. The project was scaled back to a $15 million budget. When the project was well underway, its newly appointed overseer, Minister of Trade and Commerce Robert Winters wanted to scrap it entirely and dump the prefabricated apartment units in the St. Lawrence River. Here is a photo, reproduced with permission of Safdie Architects, of the project Winters failed to stop.

Two years later, when the Liberal Party was choosing a successor to Lester Pearson, the blue (business-oriented) Liberals coalesced around Winters, and he ran second to Pierre Trudeau, receiving 954 votes on the final ballot, compared to Trudeau’s 1200. Looking back in hindsight, one can wonder how effectively Winters, a unilingual anglophone who looked and sounded like Daddy Warbucks, would have confronted the challenge of Quebec separatism. (As it turns out, Winters died of a heart attack in 1969.)

A second iconic project was the National Gallery of Canada. The existing National Gallery was a nondescript office building below Parliament Hill, a national disgrace. The new National Gallery was championed by Pierre Trudeau in his last term in office. Safdie implies that Trudeau had a role in selecting his firm and reports that Trudeau provided the impetus for quickly breaking ground, to prevent his successor from killing the project. Safdie took a key design decision to cabinet, namely the question of whether the great hall of the gallery would be oriented to the neighbourhood beyond the gallery (the extrovert option) or internal to the building surrounded by galleries (the introvert option). With no consensus among ministers, Trudeau chose the extrovert option, saying “this is the future. This is what museums will become: open and inviting to the people.” Here is a photo, reproduced with permission of Safdie Architects, of the external orientation of the gallery that Trudeau selected.

Yashar Koach, Moshe Safdie

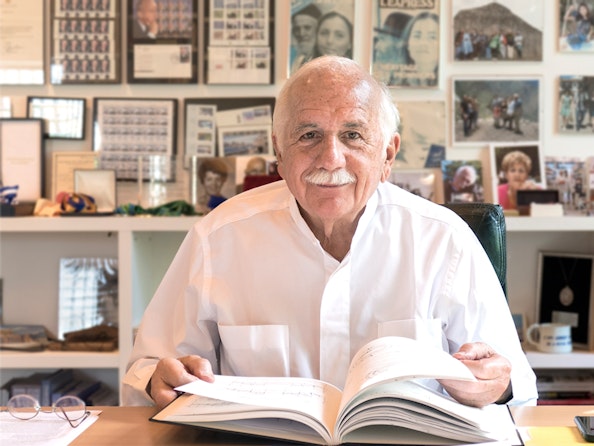

“Yashar Koach” is a Hebrew idiom that means “congratulations,” “great work,” or – my preferred translation – may you go from strength to strength. In a religious service when a member of the congregation plays a significant role, such as reading the Torah or giving a sermon or lesson, it is customary for members of the congregation to say “Yashar Koach.” Similarly, it is appropriate to congratulate Moshe Safdie for having written so eloquent and thoughtful a memoir in his mid-eighties and for continuing with his practice of architecture, going from one major project to another.

Leave a Reply